My trip to Bhopal was decided under rather unusual circumstances. On a fateful Saturday morning, I lay on the hospital bed hooked up to different machines. My gaze held the nurse prisoner. I studied her, scrutinizing each and every movement to glean information from her body language. The nervous movement of her hand as she switched off the ultrasound machine. Her expression as she whirled around to hide her face. I saw her straighten her back and square her shoulders. The room was very quiet. When she faced me again, her face was blank and her eyes refused to meet mine.

My husband stood tense by my side. His voice was tight. “What did you find out?”

The nurse answered, “I don’t know… I can’t say anything. Your doctor is on her way. She’ll be here any second.”

I knew that she knew. I knew too that my husband had no idea of what was coming. At that instant, I knew that we were going to Bhopal. I longed for home. I wanted my ammi – my dearest mother. Her loving hugs erased all hurt. I wanted my dad, who had always managed to fix each and every piece of my broken jewelry.

Today— some twenty days after the hospital stay— an empty field stretches between me and Gandhi Medical College. There are a few tombs to the west of the Medical College, and to the north, lie the remnants of the outer wall of an old fort. A warm breeze rises, carrying dead leaves and dust. Memories of the first twenty years of my life rise up and envelope me. This is the land where I started from. I am the dust that rises up from this old city, carried by winds to distant lands. I am “judge sahib ki poti” – “the judge’s grand daughter” – just as my father and his brother are known as the judge sahib’s sons. In Bhopal, all of us are known by our relationship to the late Judge Sahib.

A young boy between eight and ten years of age stands before me dressed in spotless white kurta-pajama, the traditional clothes worn by Indian men and boys. I wonder where he came from. There was nobody behind me a second ago. The boy offers the traditional Muslim greeting, “Assalamualykum.”

“Wa-alykum Assalam Wa Rahmatullah,” I reply.

I quicken my steps to catch up with my retired uncle, affectionately nicknamed Buncle, who is leading my mother, brother, sister, husband and I around the old fort. We follow him up the steps of the fort, the Qila, as he narrates the history of the Fatehgarh Qila in Bhopal. A retired professor in humanities from the Mawlana Azad College of Technology, he is well versed in the history of Bhopal.

On this trip to Bhopal, I devour the city’s history. Growing up, it never occurred to me to concern myself with the history of Bhopal or that of my family. Past and future converged in the generation of my parents. This generation knew the lineages of everybody. I met old Bhopalees at lavish weddings to renew acquaintances and this sufficed at the time. When I moved out of Bhopal at age twenty, the need to know the places and people that my parents and grandparents knew began to gnaw at me.

We walk up the faseel, the outer wall of the fort. I see old Bhopal spread out beyond the broken fortress wall. Directly below the wall, young boys play marbles. Their dusty faces flash toothy grins at me as they become conscious of my gaze.

“Here is the old fort, the Fatehgarh Fort, founded by Dost Muhammed Khan, the founder of Bhopal and named after his wife, Fateh Bibi,” Buncle says. “Later one of his descendents, Wazir Muhammad Khan, and about 6,000 Bhopalees, were surrounded by an enemy army, more than 80,000 strong. This fort had been under siege for more than nine months and bore the burdens, extraordinary sacrifices, and valor of those it sheltered … as they fought for their survival.”

Until three weeks ago, I, too, had sheltered a life for more than nine months. It, too, had fought for survival, unbeknownst to me on the Saturday that I was in the hospital. The baby, ‘Rabia,’ was named after my grandmother and also after the famous gnostic, Rabia al-Basri, who when seen running with a bucket full of water in one hand and a candle in another, was asked to explain her strange behavior. She replied, “I am going to douse the fires of hell and to light a fire to heaven to burn it down. So people can love God for God’s sake and not from fear of hell or love for heaven.” My Rabia was a beautiful baby, very quiet, very still. If only she could have puckered her rose petal lips and cried, she’d have been perfect – a perfect live baby. Strange that the cord that nourished her and kept her alive for nine months had strangled her at the end of those nine months.

Buncle continues, “At the end of these nine months, Wazir Muhammed Khan wanted to surrender. With many martyred and the starving survivors, the worried ruler of Bhopal sought the saint, Pir Mastan Shah, who lived within the fort at that time. ‘Tonight my sword lies at your feet. Tomorrow I surrender to the enemy,’ Khan said. The saint’s maqam, tomb, is over there.” Buncle pointed in a direction behind us towards the inside of the Qila. “The dervish ordered, ‘NO! Pick up your sword. Look out there ….’ The saint pointed towards the sky. ‘The star of your victory is rising.’ That night the two Maratha armies of Gwalior and Nagpur lead by the famous Scindia General Jagua Bapu and …”, Here, Buncle falters trying to remember the name.

“Mir Sadiq Ali,” the strange little boy beside me prompts with authority.

“Correct. Legend has it that Jagua Bapu’s army suffered from a massive outburst of cholera,” Buncle continues. “Mir Sadiq Ali disengaged from the fight after being reprimanded in a dream by a saint for slaughtering innocent people. Grateful, Wazir Mohammed Khan went to see the dervish again who now advised him to offer salatul-shukr, the prayer of gratitude, at the Masjid built by his predecessor and founder of Bhopal, Dost Muhammed Khan. This was the first Masjid built in Bhopal. Probably the first Masjid in the world to be built on the ramparts of a fort.”

Buncle adds with a dramatic flair, “This Masjid is also the smallest one in the world. It could not have three complete steps so they built two and a half steps, dhai sidhi, and called it Dhai sidhi ki Masjid, the Masjid of two and a half steps”

I think about the word “Dhai.” Not quite two, not completely three, but two and a half, dhai – incomplete, that is how I feel. All that love grew within my burgeoning belly for nine long months. Now, I feel incomplete with no babe in my arms to shower with that love.

Indeed, the Masjid is a very small place. We walk around it and begin to leave, even as the adhan calls the faithful to the late afternoon prayer. The steps lead us away from the Masjid and towards the parked van.

“Pray before you leave, this is the adab, proper etiquette,” the strange little boy reminds us. “Now that you’ve heard the call to prayer, to leave without praying is disrespectful.”

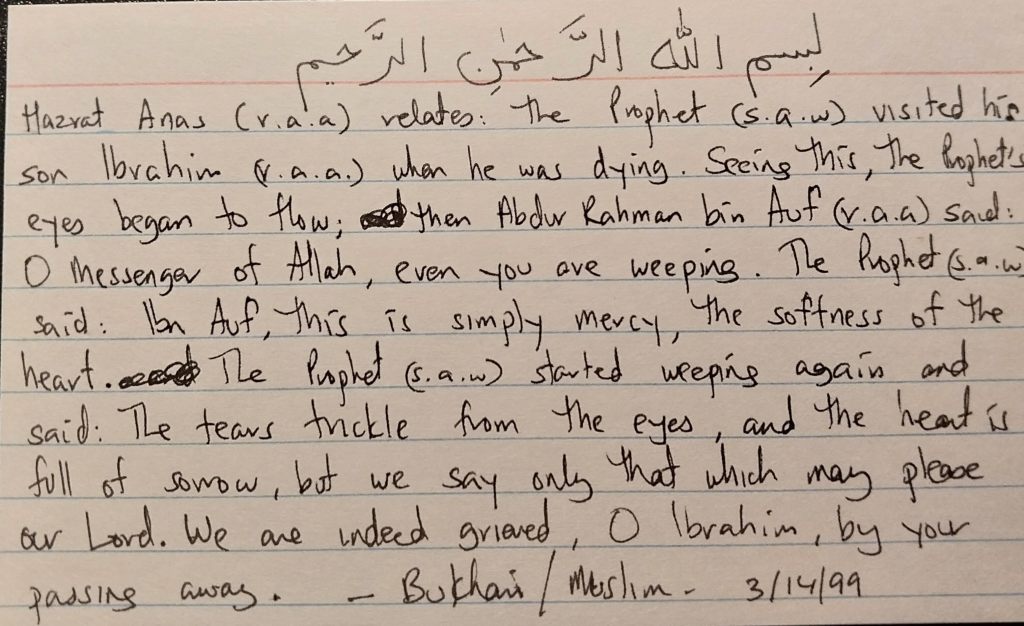

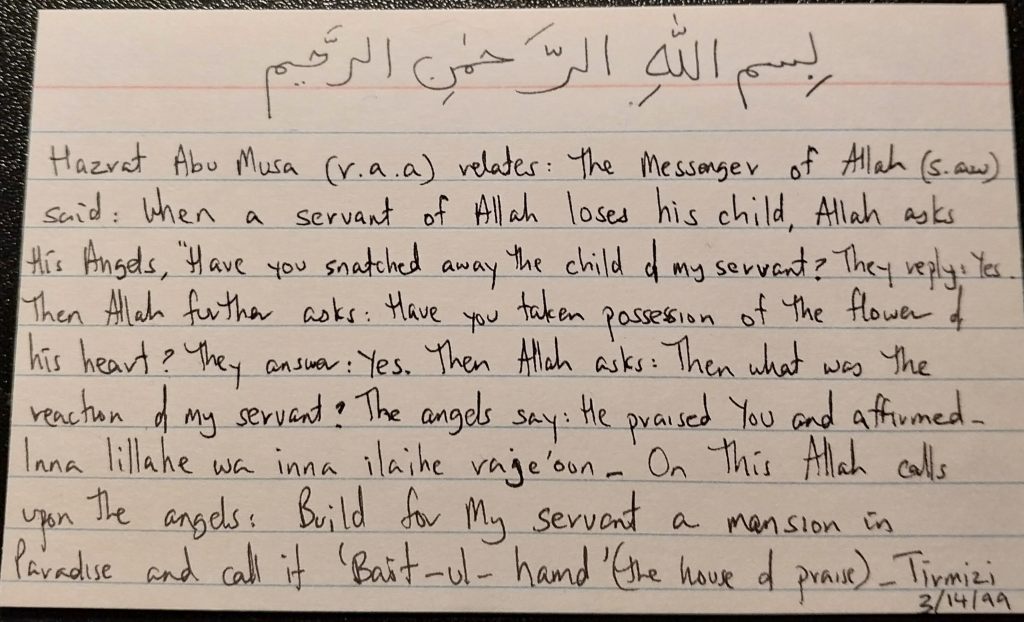

Adab? Hadn’t I remembered advice on etiquette on that dark, gloomy day? That Monday, the 8th of March, 1999. Gray clouds covered the horizon. After the funeral prayer in the spacious hospital room, we had followed the hearse to the cemetery. The rain had stopped briefly, just long enough for us to put her down in the grave. My husband’s body shook when he reached out for the little casket. Recalling lessons instilled by Dada-abba, my grand father, regarding the importance of good adab with God, I whispered to my husband, “Alhamdulillah hi ala kulle haal – praise be to God under all circumstances.”

Buncle praises the mysterious boy. “He is right. We should pray before we leave.”

All of us turn back towards the Masjid. Half a dozen children fill the Masjid. There is barely enough room for the three men to squeeze themselves in. Together with my mom and sister, I go back up the fortress wall. We pray and wait for the men to return.

The little boy is the first to arrive, followed by my husband. I motion the boy to come close, so I can quiz him. He answers each question gravely. He tells me that he stays with his grandmother while his father, who is a laborer, goes to work during the day. I ask him why one of his eyes is red. He shrugs and replies, “It’s just like that.” I want to know more about this mature little person. Both of us— my husband and I— are fascinated by the boy. When we run out of questions to ask him, he sits quietly, uninterested in us. Odd, considering that he has accompanied us all this time. We continue to sit on the parapet, listening to the boy’s silence.

My sister has her arm around my mother. They observe us with compassionate faces. My mother’s light brown eyes shine with fresh, unshed tears. Earlier today, she told us of her shock upon learning about Rabia. She cried sitting by my side, hugging me while I tried to soothe her. Pointing in the direction of me and my husband, she had said, “My children’s pain is more painful than my own.” Ammi also told me that on that fateful day, early in the morning at fajr, the dawn prayer, my dad had declared, “My heart is heavy; I am feeling sick. I think someone very close to me is suffering from a great difficulty.” He had spent the entire day praying and meditating. In the evening, my parents had received the telephone call.

Now, Bhopal prepares for sunset. It is my city, my home, but the road is new to me. Everything looks the same, yet the meaning of these familiar things has changed. The lake nestled in the valley between Shamla and Eidgah hills still reflects the beauty and the mood of the surrounding world. Now, the lake mirrors the sun as it passes on to a new life on the other side of the world. This passing will plunge Bhopal into darkness— just for a while though. Then the people will rise again to meet their beloved sun.

Indeed, the world has not changed. I have. In this new, subdued landscape, where nothing is taken for granted, I am learning to hide my grief. I pretended to be my old self by feigning interest in jewelry and dresses to make my mother happy. I say, “Shukr lillah, all thanks to God” when my mother seems pleased at my purchase of dozens of shiny bangles at the Bhopal chowk. I am also learning to comfort my parents. I spent the entire forty-eight hour journey to Bhopal with visions of collapsing in their arms, of crying my heart out, of letting go and being comforted by their all accepting embraces. This is what I expected. But I found myself comforting them just as they used to comfort me when I was a child.

Now, sitting on the parapet with my husband, I see swaying branches in the distance. I remember looking at swaying mango branches in my courtyard as my grandmother, Dadi-amma, reminisced about her late husband, my Dada-abba, when I was a young girl. “Your Dada-abba merhoom was a district and sessions judge. A very pious and learned man, indeed. Twelve years ago he left me to face this world all by myself. You were six months old when he passed away.”

“Did Dada-abba used to hold me and play with me?” I asked with the eagerness of a thirteen year old.

She replied with a nod. “He loved you very much. At your birth, he was the one who called out the adhan in your ear.” She noticed with satisfaction that I was very pleased with the news of this honor and continued, “He used to sleep the first third of each night, the final two-thirds, he spent in worship. He used to recite a lot of salawaat, blessings on the holy Prophet, and blow these prayers on you all the time. When he was not retired yet and the time came for him to make a judgment on a case, he stayed up the whole night, crying and praying. He would prostrate and ask Allah Al- Haadee, The Guide, Al-Adl, The Just, to guide him to a just decision. It is a record that none of his sentences were ever overturned, even though the cases were sometimes appealed in the higher courts. Those were the days… your Dada-abba had a special presence.”

“And a special absence,” I thought to myself as I browsed through the book shelves in my house. Most of the books opened up to reveal his name in an upright, beautiful handwriting. The name, ‘Muhammad Afzal Kureishy,’ was penned with a flourish, in once black ink, across the yellowed pages.

Dadi-amma sighed and continued, “Your Dada-abba’s piety shone through his every day actions. Each morning around ten, your Dada-abba would step out of the house with a basket full of fruit. The little children in the lane knew the routine and would run up to him for a treat.”

I see little children running out of the Masjid after finishing their prayers to resume their game of gilli-danda. Buncle seeks us out on the faseel, the rampart, after he finishes his prayers. His handsome face creases into a smile as he smoothes his hair, which has more salt than pepper. It is as though he can hear my thoughts about Dada-abba.

“Your Dada-abba,” he says, “after retiring as a district and sessions judge served as awqaf commissioner in 1957 and ‘58. The awqaf, or the waqf board, looked after the administrative and financial needs of the Mosques. In the 1850s, Her Highness the ruler of Bhopal, Nawab Shah Jehan, Begum of Bhopal ordered the awqaf to include churches and Hindu temples. She was the third of the four generations of women who ruled Bhopal from 1819 to 1926. Your Dada-abba knew that the awqaf was planning to close old Masajid that were not in use anymore. This could save the government some money on maintenance and clergy salaries. The Dhai Sidhi ki Masjid being so small was not much in use those days.”

Buncle continues, “The adults of the families that lived here would go out during the day to earn their livelihood. They prayed in whatever Masjid was near their place of work. This Masjid was not always occupied. Your Dada-abba came here and explained the situation to the imam. He advised him to let the children come to the Masjid at all times. Dada-abba then went to people’s houses around the Masjid. He told them to send their children to the Masjid, to keep it busy so the government would not shut it down. Since that time, the children of the neighborhood can be found praying and playing in and around this Masjid.”

Dada-abba is gone now. None of children playing here know about Dada-abba. Neither do the families that live around here. The visitors to the mosque are oblivious of the memories that ooze out of its white-washed walls. I feel a kinship with this building of stones, lime and clay. Our hearts share a common bond.

The little boy nods his head in agreement to Buncle’s story. We say salams to the little boy and leave the Masjid.

In the van, I blurt out, “What was he?”

“A jinn in the service of the saint, Mastan Shah.” Buncle replies, “The saint is gracious and kind towards us for some reason… perhaps because of your Dada-abba. He sent his khadim, servant, to take care of us.”

“You’ve been here many times. Have you met him before?”

“Yes, but in different forms. One time, he came in the guise of an old man.”

It is dusk as my brother starts the van. Shopkeepers have switched on lights in their shops. The man pushing a thela, a hand cart half loaded with small ripe bananas, calls out to people to buy his fruit. The lone cow by the roadside decides at this moment to move out in the middle of the road, making the black and yellow auto-rickshaw brake hard and honk. The sparrows swoop upwards and fly away. One last time, the breeze teases bits and pieces of paper lying on the road.

I close my eyes and hear the sonorous voice of Hafiz Sahab, my Quran teacher, as he explains the three created beings. The Angels are created from noor, light. These are pure beings with no will of their own, therefore always in a state of perfect obedience to their Lord. The Jinn are created from fire, free of smoke. These are energy beings co-exisiting with the humans in the same space, but in a different dimension. Since Jinn are energy beings, they can assume different shapes. Finally, humans are created from clay and endowed with free will like the Jinn. I recall Hafiz Sahab reciting the verse from the Quran-e-Kareem in Arabic. His beautiful rhythmic chant drifts in over the many years that try to separate us. A thirteen year old version of myself sits demurely in front of him. I am clad in a shalwar kurta. My head is covered in a dupatta. My teacher sits in-front of me against a backdrop of white arches on the long verandah. He is dressed in a white kurta pajama. His head is covered with a white topi or cap. The fragrance of the mogra, jasmine, hangs heavily as the shadows start to lengthen. A copy of the Quran-e-Kareem is in my lap. My gaze follows the words he recites. I listen, longing to someday recite perhaps as beautifully as he does.

Later that night, I gaze at the dark sky trying to spy some stars. I recollect the times in my life, Dada-abba has reached out and helped me. At eighteen, I had dreams of heading west and chose to interview at the Canadian embassy rather than appear for my college exams when dates for both events coincided. Though this decision shocked my parents, both professors, they had traveled 500 miles with me to Delhi for my interview at the embassy. During the return trip, on the train, I sat quietly trying to absorb the consequences of the interview. The Canadian official had rudely informed me that she was denying my visa to Canada. I was devastated. Missing my exams meant that I would have to repeat the entire year of my studies while my friends continued on without me.

That night, on the train, I dreamed of my Dada-abba. He was sitting and grieving for his oldest son, Aslam, who had died a tragic death in a shooting accident at age eighteen. In the dream, Dada-abba made my heart experience the state of his heart. Dada-abba was grief stricken, yet his heart did not complain. His heart was at peace and it chanted, “God is the Greatest.” I woke up to find my heart at peace and it, too, chanted, “God is the Greatest.” When I told my dad about my dream, he interpreted it, saying, “Your Dada-abba had good manners with his Lord. This is important especially at times that test your mettle. In your time of sorrow, Dada-abba came to help you. He is instructing you to recite ‘Al-Mutakabbir,’ an attribute of God which emphasizes His Greatness. This to ease you through a difficult phase of your life.”

Trying to fall asleep, I conceive of ways to ease the pain in the present phase of my life. I am rewarded as the clouds move and the dark sky blazes with bright stars. My thoughts wander to Dadi-amma. Until I was nineteen, she was a part of everything I’d done in my life. I hadn’t realized how much I loved her until long after she had passed away. She had bridged me to the life and times of Dada-abba and taught me to love and connect with loved ones in a different realm. During my pregnancy, I dreamed of her frequently, perhaps subconsciously trying to link my unborn child and my grandmother across different generations and different realms.

I fall asleep wondering about lives of those gone by and lives of those yet to come. I dream again. In my dream, I see my Dadi-amma dressed in beautiful silk pastels. Dadi-amma is young and beautiful. She bathes my daughter Rabia.

Fa Be ayye alaaye Rabbikuma tukazzebaan

Then which of the favors of your Lord will ye deny?

Of Him seeks (its need)

Every creature in the heavens

And on earth:

Every day in (new) Splendor

Doth He (shine)!

Then which of the favors of your Lord will ye deny?

Fa Be ayye alaaye Rabbikuma tukazzebaan”

The Gracious, Chap. 55: 29-30

Some fourteen hundred years ago, when the Prophet (peace be upon him) recited these divine words, the Jinn had responded,

“La bi shai’in min ni’mati Rabbi-na nukadhdhib:

‘We do not deny any of our Lord’s blessings’.”

Leave a Reply to Nooreen Jilani Cancel reply